How an air crash investigation in Germany uncovered the story of one of the most secret spy operations of World War 2

A mysterious crash

In the small hours of the 20th of March 1945, Olinde Kruse woke up from the sound of a loud crash. Startled by the sudden bang, she sat up in her bed, listening on, holding her breath – but nothing further could be heard in the quiet of night. Her husband, Bauer, was still in deep sleep beside her, exhausted after a hard day’s labour in the fields. He didn’t seem to have noticed the loud noise at all. Hermann, their 6 year old son was still asleep in his bed across the room too. Olinde was very tired herself after a long day tending to the farm, and thinking it must have been the last thunderclap of the storm passing over the Schwege moors, she promptly went back to sleep.

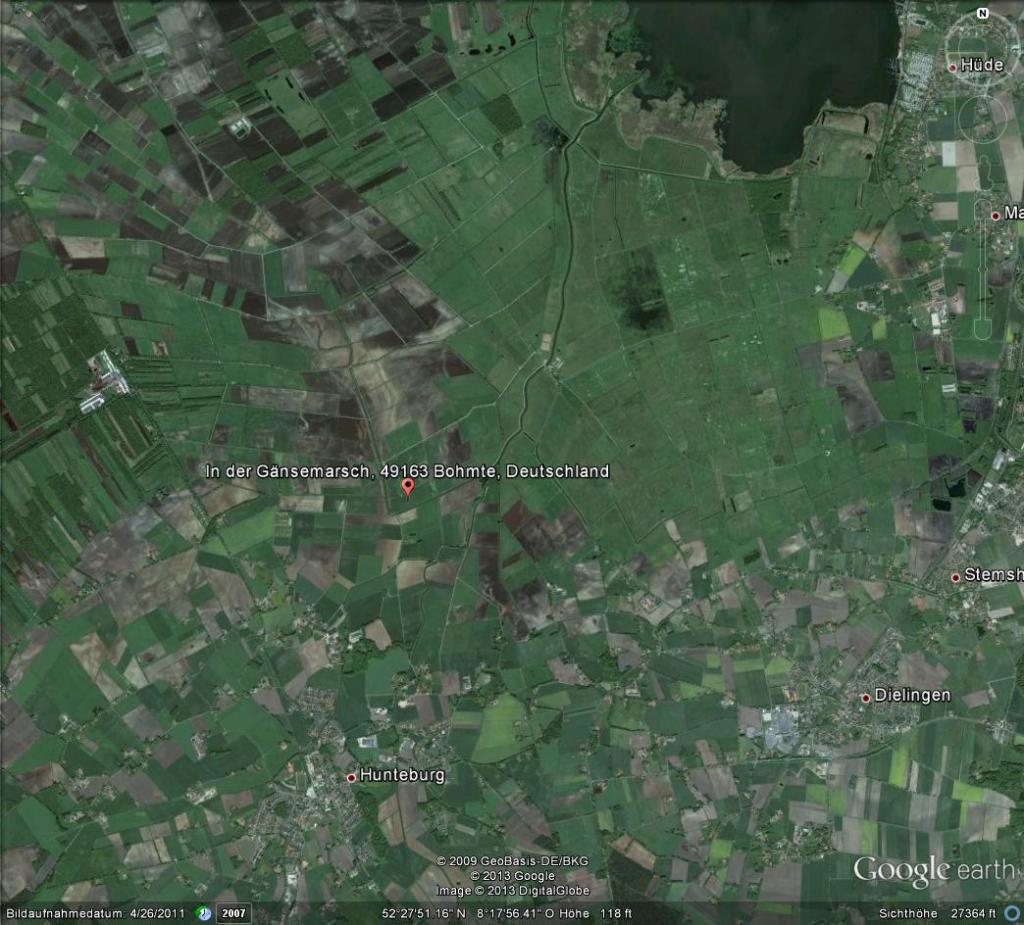

The farmstead outside Hunteburg (a small town near Osnabrück in Lower Saxony), belonged to the Kruse family for generations. It meant hard work every day, but especially in recent years, ever since all the young men who used to work for them had been called up for military service. The state had sent replacements in the form of able Russian and Ukrainian prisoners of war, who now helped working the fields and tending to the animals. They didn’t speak much German, but they were capable farmers.

The following morning, Olinde discussed the curious incident with everyone at the farm. Some workers had been startled by last night’s noise too, raising further suspicions about the nature of the loud crash. In the afternoon, after the day’s tasks had been completed, Olinde, young Hermann and a Russian hand set off through the fields, heading towards what she thought was the general direction of the bang she’d heard the night before.

As they approached the lakeside of Dümmer See, they arrived at a scene of carnage : before their eyes, there was the mangled metal hulk of an unmarked black aircraft, part-buried in the marshland – and on the left side of the wreckage, lay the dead body of an airman, badly wounded in the left leg. The body of another airman could be seen in the meadow about 50 metres away. A third airman could be seen in the water, a bit further away, while a fourth member of the crew was eventually discovered at a distance of about 100m from the crash. They were all bearing US insignia.

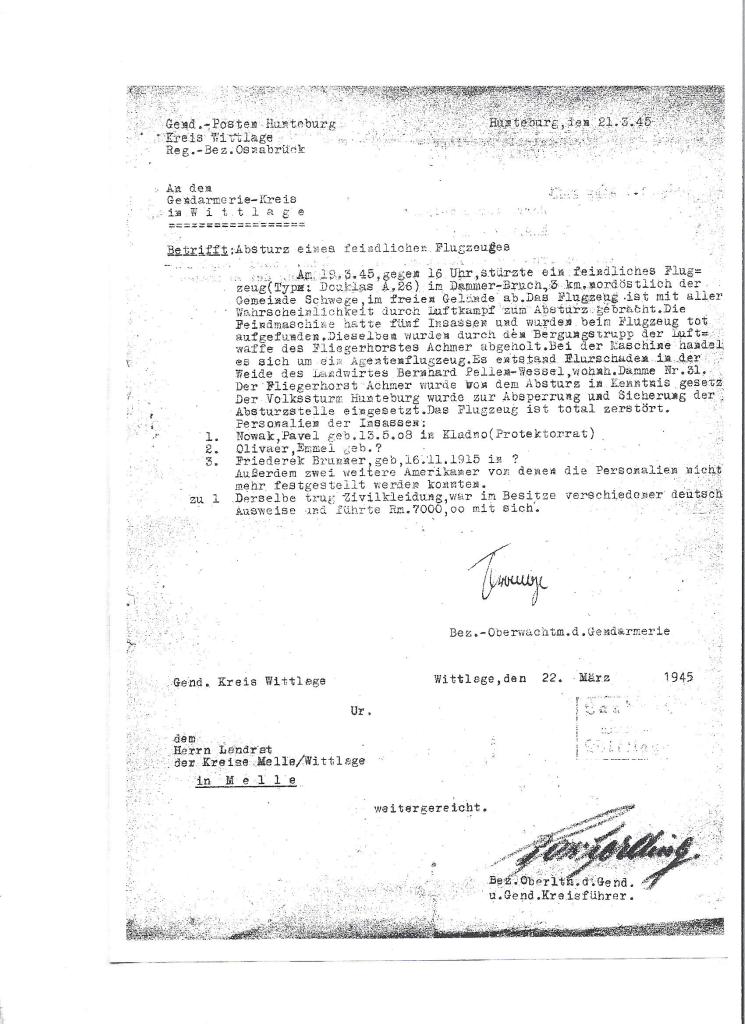

On the right side of the wreckage, the Kruse family made an unexpected discovery : the body of a man dressed in civilian clothes, bearing a fatal wound on the side of his head. The papers found on the body identified him as Pawel Nowak, a Czech citizen. He carried documents from the Hermann-Göring works in Prague, recommending him for work in a factory near Mülheim in the Ruhr Valley, Germany’s industrial heartland.

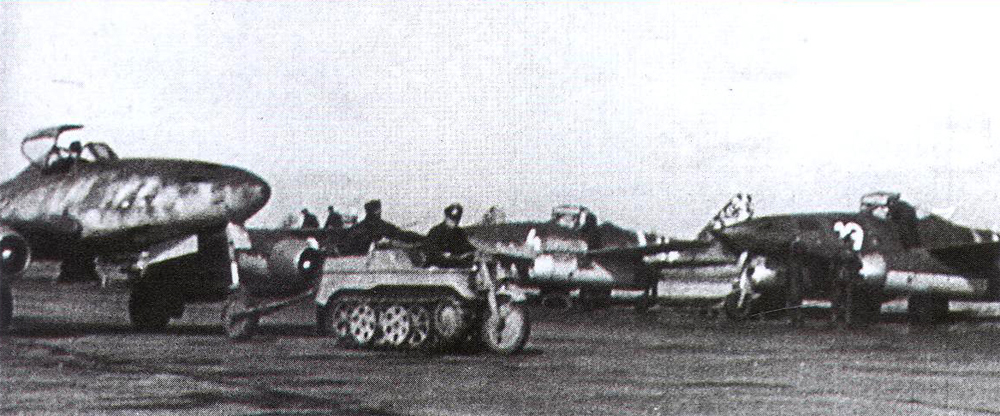

The family alerted the Gendarmerie at Bramsche, about 30km away, who promptly reported the incident to the airbase at nearby Achmer. Wonder Weapon aircraft like Me262 and Ar234 operated there in the final stages of the war, and the skies over the marshland frequently buzzed with the unfamiliar sound of jet engines.

Before long, a Luftwaffe rescue contingent led by officer Ernst Grussendorf arrived at the scene, removed the bodies, and confiscated documents and other evidence from the crash site. With the help of Luftwaffe’s British and American Aircraft Identification Manual, the wreckage was identified as a US aircraft, initially thought to be a Douglas Boston. The offices posted a number of Hunteburg’s Volkssturm – the local militia – to guard the crash site overnight. A few days later, they brought in heavy lifters and removed the wreckage to the airbase for inspection.

By the end of the investigation, authorities had realized that this was a indeed a more advanced aircraft type – a Douglas A-26 Invader. The bodies of the deceased airmen were interred with full military honours at the prisoners of war cemetery close to Achmer airfield – and alongside them, the body of the civilian Pawel Nowak. For the next 70 years, the nature and circumstances of the crash remained a mystery, and so did the unexplained find of a Czech factory worker among the crew of the crashed US aircraft.

The search

It’s a cold winter day in February 2015, and Gertrud Premke had been knocking on doors and accosting people on the streets of Hunteburg all morning. The freelance journalist, reporting on behalf of local media group Wittlager Kreisblatt, was an avid researcher of local aviation history. She had been following up on a cold case from WW2, the rumour of an American airplane crash in the marshland near lake Dümmer. The crash itself wasn’t unusual : the lake was a substantial body of water, and flyers frequently used it as a visual navigation point. Allied bombers flying in from Britain especially favoured it : once they trespassed into occupied Europe through the reasonably flak-free Zuider Zee corridor in the Netherlands, they would turn east by southeast at Dummer Lake. It was a manoeuvre that lined them up with targets at Hannover, Braunschweig, and Magdenburg, before reaching Berlin. As a result, several aircraft, both Allied and German, were known to have crashed in the region around lake Dummer, whether by flak, weather or accident. For her investigation, Premke had teamed up with the one person who was familiar with every single one of those incidents : Martin Frauenheim, a local aviator and aviation historian, who was also a known air crash investigation authority in the region.

Frauenheim reveals : “I was born in 1947, and been married for more than 50 years. I have with two adult children and four adult grandchildren. I studied Mechanical Engineering, and worked at a machine factory for railway signaling technology – but it was aviation that fascinated me since I was a child. I have been a member of the Osnabrück-Atterheide Aeroclub since 1972, and have spent the last 60 years building a collection on Osnabrück’s aviation history, in particular the story of local rocket pioneer Reinhold Tiling. My many years of voluntary work as mayor of our municipality of Hagen am Teutoburg Forest, resulted in many local contacts, from whom I have learned a great deal about the region’s Second World War history. Through the years, I have also been involved in aviation archaeology. In addition to the numerous plane crashes recorded near our local community, crashes in the greater region have also been extensively researched and documented.

I became somewhat known locally for my involvement in air crash investigation & research. So some years ago, I received a tip about a WW2 plane crash in the region – one that involved a secret agent. All experts following up that rumour up to that time considered it unsubstantiated, a cold case. But this very fact stoked my own curiosity further ! It took about a decade of meticulous research before all the facts finally surfaced. ”

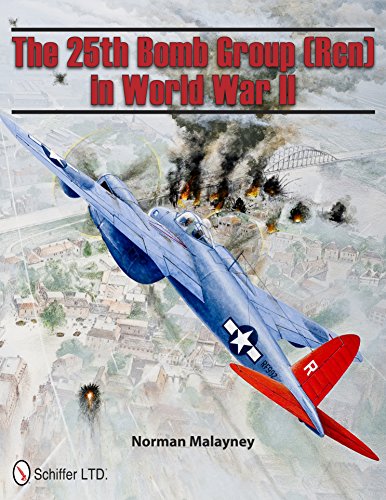

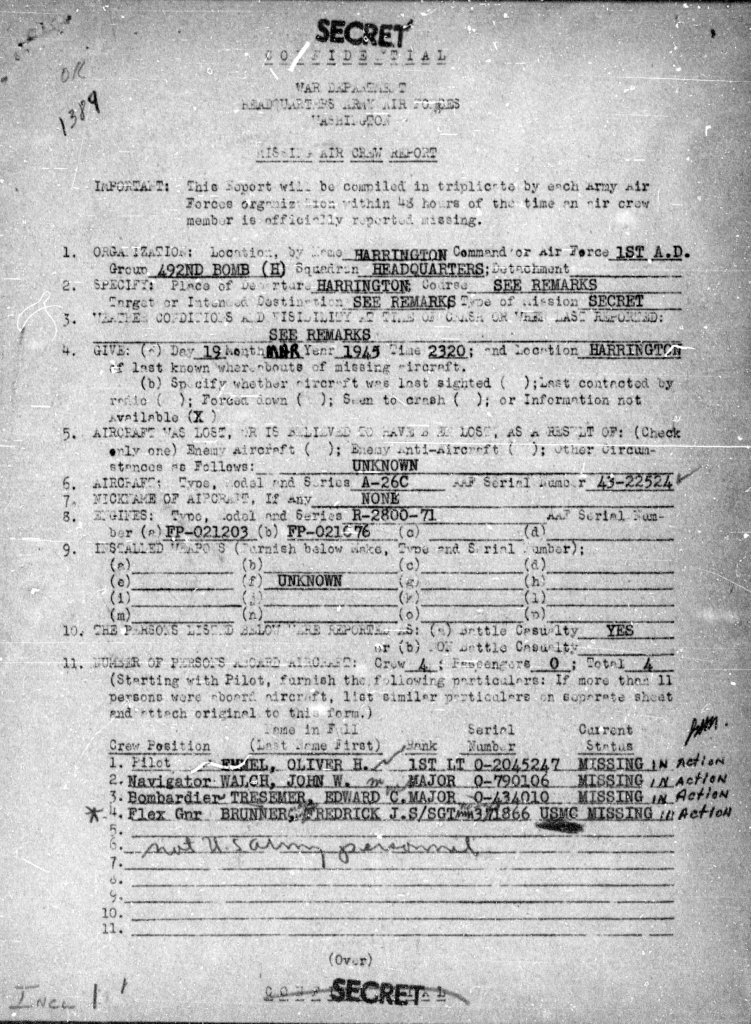

After teaming up with Premke to look into the case and cross reference newly declassified documents, Frauenheim came to realise that this particular crash was different. US Air Force documents from the 25th Bomb Group (Reconnaisance) recorded the lost aircraft after it failed to return from its flight. But previously unknown facts about the true nature of the activities of 25th BG had began emerging around 2010 : specifically the use of its aircraft to insert secret agents into occupied Europe, and then harvest the intelligence they transmitted via radio. Both of these missions required stealth, and so the groups “special” squadrons were equipped with the latest, fastest light bomber aircraft available to the Allies at the time : DeHavilland Mosquitos and A-26 Invaders. Painted pitch black, and bearing no insignia, the aircraft could fly deep into enemy territory at night in relative secrecy.

Frauenheim recalls : “..the hitherto completely unexplained nature of the crash was the incentive for a detailed investigation. At first there very few clues to follow up. But then came the publication of a book – “The 25th Bomb Group (Rcn) in World War II” by Norman Malayney An aviation friend had given me a copy, and in it, I found the first references about the lost Invader mission in March 1945. Eventually I got in touch with Norman Malayney, who has kindly corresponded with a wealth of information and material on those secret missions over Germany. I am grateful to Malayney for his valuable insight – finally, some well-founded clues and hypotheses about what might have taken place that night began to emerge.”

The declassified manifest of the Douglas A-26 Invader as well as the missing aircraft report specified 4 crew members unaccounted for – 3 airmen and a US Marine Corps Sergeant. However, those didn’t match the German incident and eyewitness records. Those records mentioned confirmed that a 5th body had been recovered from the crash, identified as a Czech civilian, Pawel Novak. So what was the answer to that mystery ? What really happened that night ? The researchers knew that in order to answer this, they first had to locate the crash site. And sometimes, it seems, all you got to do is ask.

That was the reason Premke turned up at the village that February morning in 2015, asking around local stores, businesses and passers-by about whether they had any memory or information about the airplane crash that happened near the lake in March 1945. She knew from existing archival records – Olinde Kruse’s and Ernst Grussendorf’s official testimonies – that the plane had been found near the Kruse farm, and after inquiring with a number of locals, she was directed there. As Premke reached the farm, she saw an elderly man driving a tractor, and waved him down. The elderly man’s eyes lit when Gertrud Premke revealed the nature of her visit : the 76 year old was no other than Hermann Kruse, the little boy who, alongside his mother, had witnessed the aftermath of the crash in March 1945. Kruse still lived and worked his family’s land 70 years later, and the horrific memory of what he witnessed as a 6 year old child was still very much with him. He promptly led the researchers to the brook where he remembered seeing the wreckage all those years ago.

The dig

Frauenheim, Premke and a group of volunteers began scouring the exact spot pointed out by Kruse. Soon, the scanners began picking up metal signatures in the wider area next to the brook.

This was, beyond doubt, the missing A26 Invader that crashed in the marshes on that fateful night in March 1945. But what could have been the cause the crash? Frauenheim had already been developing a well rounded theory about what might have happened :

“After a lengthy search for the crash site, we finally found the exact location of the event, thanks to information provided by two surviving eyewitnesses. Although the crash site was cleared at the time, everything that penetrated the ground due to the force of the impact could still be found today by scanning and probing. The subsequent dig at the site brought extensive material to light, which enabled us to make an exact match of the aircraft involved. The discovery of the nameplate of the machine at the crash site was the highlight of the dig, and a real stroke of luck. The crash site investigation was spread over several weeks and even across seasons, due to the realities of the site being used as arable farmland. Our search could only take place after the harvest, but it resulted in the discovery of countless small aircraft parts, which I itemized and photographed meticulously prior to assigning those to the schematics and structure of the aircraft. With time, we were able to determine even specific flight instruments from the fragments found at the site.

It was hinted somewhere that the aircraft might have been unarmed. However, we found hard core 12.7 mm rounds, which could only have come from this aircraft. A contemporary witness confirmed that the entire wreckage was painted glossy black on the outside, without insignia of sovereignty. He also described how the tail rudder was made of fabric, just like the elevators, rather than aluminium – an important identifying detail. We also found a small sealed glass tube. Could it have been some form of soluble drug? I suspect that amphetamines could have been used by aircrews to keep them sharp during longer night missions. Further analysis would be required to confirm this assumption.

“(Back then as it is today) ..every aircraft was routinely subjected to a safety check after it has been flown and used between 50 and 100 hours, and particularly crucial parts are immediately replaced when found to be defective. It was probably the same with this Invader. The aircraft should have been thoroughly checked before the mission, including the possible replacement of both engines – which could have been shot up by flak during its previous mission. But due to a confusion over its final orders on the day of the flight, there was a great deal of hectic activity, which suggests that the technical checks were carried out hastily. A test flight usually follows a technical check-up, but in this case, none of those seem to have been carried out thoroughly enough, or even at all. In addition, the crew was inexperienced, and had never flown missions together before. The pilot himself didn’t have much flight time at the cockpit of an Invader. Last, it is surprising that this flight was in our area despite the adverse weather forecast. So, hypothetically, many of the the failures that led to the crash could have been avoided.

The operation would have involved low-level flight at night, indicated by the matt black paintwork for camouflage. The low level flight is assumed because German anti-aircraft guns wouldn’t be able to depress their barrels enough to shoot in such a steep trajectory. But low level night flights pose particular challenges too. Eye witnesses reported that the wreckage didn’t appear to have exploded on impact, and it didn’t look burnt out either. However, we did find charred engine parts at the site. My guess is that there might have been an engine fire prior to the crash, forcing the pilot to shut down the engine and trim the aircraft for single-engine flight. But it is likely that the aircraft was flying too low to cope with the loss of one of the engines. It possibly got into an incline, and its wing caught the ground at full speed, cartwheeling sideways with the terrible consequences witnessed at the crash site. Had the aircraft been flying much higher, they could have used the parachutes (they had already been wearing) to survive..”

Later revelations would affirm Frauenheim’s hypothesis to a great degree. But the mystery of the identity of the Czech civilian was soon to be revealed too. And none of this could have ever been possible if it wasn’t for more recent developments in the declassification of OSS documents pertaining to the agency’s wartime activities.

Glimmers of Light

Around 1980, the CIA transferred all Office of Strategic Services (OSS) files held in their vaults since wartime to the National Archives & Records Administration (NARA), with a view to begin the process of their declassification under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act. The records contained detailed information on every clandestine operation performed by the OSS during WW2, including the names of the agents and personnel involved. Slowly at first, the nature and scope of OSS secret effort to penetrate the 3rd Reich was gradually being revealed.

In 2002, a New York lawyer named Jonathan Gould began publicizing the memoir of his father, former OSS Labour Division Leutenant Joseph Gould. The story he revealed was rather incredible : it appeared that in the final stages of the war, the OSS, under pressure to provide credible intelligence ahead of the Allied advance beyond the Rhine, had sought to train exiled German Communists for the task. The so called TOOL Missions were a fact : Lt Joseph Gould himself was the man who sought, recruited, trained, and then successfully launched those men into Germany. For his service, the OSS recommended him for the Bronze Star in summer 1945. By October that year, however, the OSS had ceased to exist, and was replaced by the CIA. With the Red Scare, McCarthyism and Cold War mistrust on the rise, intelligence work was fast adapting to a new post- war environment. At some point, someone high up in the hierarchy decided that the inconvenient details of this unholy wartime alliance with Communists should rather remain secret. So the commendation was never pursued, and Lt Gould had still not received the Bronze Star Medal at the time of his death in 1993. This injustice prompted his son, Jonathan, to make his story known, and petition for a posthumous award. After a long campaign, during which Jonathan uncovered a trove of formerly classified OSS documents about the TOOL missions (not least the original 1945 medal commendation for his father !) the well-deserved Bronze Star was finally awarded by New York Congressman Charles Rangel.

Jonathan’s efforts, however, had begun revealing much more than the story of his father. Through the archival research of declassified documents and interviews with survivors and their relatives, the stories of the men who took part in those top secret clandestine missions began taking shape, in glorious detail. As early as 2002, Jonathan published a clue about one of those men, Kurt Gruber “..killed when the US Air Force plane carrying him to his destination in the Ruhr Valley crashed in bad weather on 19 March 1945”

Martin Frauenheim recalls “The name Kurt Gruber and the “Free Germans” were completely unknown to me for a very long time. For many years I only had the aircraft’s declassified casualty report, as well as the police incident report, initially sourced by Dutch researcher Jan Hey, an expert in the field. Even him, however, could not provide further details before he sadly passed away a few years back. But I was already becoming familiar with the name of Lt. Joseph Gould, a name that kept turning up in declassified documents about the March 1945 crash. One thing led to the other : eventually I discovered the name and address of his son, Jonathan Gould, as a result of an Internet search. When I asked him about the events surrounding the crash, he immediately got in touch and provided me with further information. He was equally grateful that in this one case we were able to provide a great deal pf accurate information about the location of the crash.”

“The publication of his (Jonathan’s) book brought many more names, dates, facts about operations over Germany at the end of World War II. His extended research revealed a host of other secret agent missions in and around the Osnabrück area, which fortunately went on without incident.“

Frauenheim began corresponding with Jonathan Gould in March 2015, shortly after the discovery of the Hunteburg crash site. By that time, Gould had began turning his father’s memoir into a book, and was already in possession of substantial declassified material about the “lost” CHISEL mission. It soon became apparent that Pawel Nowak, the Czech national whose body was unexpectedly found among those lost in the fatal air crash, was the same person as exiled German dissident Kurt Gruber, whom Lt Gould had trained and instructed into an OSS agent at the Franklin Mansion in Ruislip, England between late 1944 and early 1945.

“Kurt Gruber had been trained to present several identities as part of his agent assignment, and that complicated my research for decades, making it hard to connect the dots. But once we had established his real name, we found the first solid traces of his identity through making contact with his birthplace at Ahlen in North Rhine – Westphalia. Kurt’s brother Karl, who was also a communist, had been murdered in a street fight by Nazi paramilitaries in 1931 under a trivial pretext – for being a protester. His funeral was attended by everyone in his town. Kurt Gruber took his brother’s death as a sign to go into hiding and begin his resistance activity. Their story stirred enduring sympathy within the local community, where he is still remembered to this day.

Through my research into Gruber’s life and deeds, I became familiar with the Free Germans and their activities. Defying the Nazi regime at that time was an act of extreme courage. Joining these secret missions voluntarily shows a very clear determination to oppose the Third Reich. It would be desirable if the United States erected a memorial at the crash site. The premise of German communists supporting American clandestine operations is unique, and deserves to be commemorated. That would certainly be a difficult decision for the Americans to make, however there is merit to it since four American crew members also lost their lives.”

Special thanks to Martin Frauenheim for sharing the details of this astonishing story and his detailed research on the Hunteburg Crash. All photos and documents in this blog post, unless otherwise specified, come from his personal archive

Disclaimer : The dramatization of the night of the crash is entirely fictional, loosely based on all available data. The sole intention of this dramatization is to add flavour in the presentation of the events surrounding the crash.

Thank you for putting this presentation together. I picked up some interesting additional information. Clive Basset at Harrington introduced me to the Facebook page.

LikeLike

I am really glad you’ve made contact. Martin Frauenheim,, the German researcher who discovered the crash site is very keen on getting in touch. Please email me at explore@explorabilia.co.uk

LikeLike

Hello altogether, it is right…Martin Frauenheim put all the presentation together in 2022. My name is Gertrud Premke and as mentioned in the article I am the free lance journalist who made the researches in the litte village Hunteburg and met Herman Kruse first time and he showed me the place of the mysterious aircrash and told me the story, experienced as a 6 years young boy. The second meeting with Hermann Kruse was together with a team of men incl. historians ( as Martin Frauenheim) and 2 professionals with detectors and we found pieces of the crashed aircraft. Later I wrote a newspaper article in our locals newspaper Wittlager Kreisblatt and sent a copy to the air-museum in Harrington. Then I took up contact to Jonathan Gould, a solicitor in New York. He had the long- time intention to write a book about the OSS ( and make possibly a film) the book was completed in 2018 incl. the Gruber story . We telephoned many times during he worked on this book ” German Anti- Nazi Espionage in Second World War”. Shortly after finishing this troublesome work which had started already 20 years ago, Jon Gould deceased. I would recommend to read his “life-work” which reveals a lot of the unknown of the Free Germans and Nazi-Germany. Unfortunately Jon Gould did not experience anymore a afilming of the book-contents. Gertrud Premke

LikeLike

Dear Gertrud, thank you for contacting me here (and apologies for missing the notification of your message for several months).

Your phenomenal research work on the Invader crash popularized the nearly forgotten history behind it, and preserved it for future generations.

I have been in contact with Martin Frauenheim in recent years, and he has kindly shared his archive with me.

If you’re up for an interview to discuss the Invader research and beyond, please contact me at explore@explorabilia.co.uk

Werner Fischer is still missing outside Leipzig, perhaps he can be found

LikeLike