Miner, Communist, OSS Agent : the short life of the Free German who trained in Ruislip during WW2

A cold wind sweeps over the vast war cemetery at Neuville-en-Condroz outside Liege. Snow twirls, teeth rattle and hearts groan in the vast field where 5300 young men are buried. Many of them are men who fell during the bitter fighting in the last winter of the war in Hürtgenwald, or the Ardennes, or crossing the Rhine into Germany. Over half of them are U.S. airmen, brought down from the skies during the bombing campaigns that devastated the Reich in its final days. The cemetery has 11 cases of brothers who died side by side in the fighting… among the endless array of crosses, blocks, and stars of David, one can find the graves of Kurt Gruber and the fateful crew of the secret CHISEL mission that was lost over Germany in March 1945.

Germany

The story of Kurt Gruber begins in the coal mining town of Ahlen in Westphalia. Its major colliery and proximity to the Ruhr industrial area saw Ahlen grow rapidly in the early 20th century, attracting a diverse, multicultural worker population. By the 1920s, bad working conditions, low social status, and poverty, had become common sources of discontent among Ahlen’s miners. Then, a serious accident at Westfalen colliery’s shaft 2, cost the lives of 14 miners. By 1929, following a decade of demonstrations and strikes, the local branch of the German Communist Party (KPD) had become the dominant political force in the city’s council, with 24% of the vote.

The young Gruber brothers, Kurt and Karl, were Ahlen miners and active members of the local KPD. By 1930, however, the Nazi party had become the second largest in Germany, amidst the rampant financial and social crisis that characterised the Weimar Republic. Thriving in that environment of discord and political uncertainty, Nazi militias began to take law in their hands. On March 24th 1931, during another meeting engagement between Nazis and Communists in the streets of Ahlen, Karl Gruber was shot, and killed. His funeral was attended by 3000 people, nearly the entire miner population of the town, and was the largest demonstration Westphalia had ever seen. In February 1933, four months after Hitler had been sworn in as Chancellor, the Reichstag is mysteriously destroyed by arson. Hitler points the finger at the Communist party, and the persecution of KPD intensifies.

Gruber’s anti-fascist activity has also intensified in the aftermath of his brother’s death, and his KPD membership and involvement in various acts of civil disobedience has made him a target for security services. In 1935, the Party helps Gruber emigrate to Prague, where he continues to resist as a courier for confidential communications to Berlin – a trip he appears to have undertaken at least 10 times, putting himself at great risk. On his last trip as a courier, he reportedly

stepped off the train in pre-war Berlin only to be confronted by wanted posters with his face on them all along the platform.

Realising that Gestapo officers were waiting at the exit, he ran for his life – only escaping after a tram driver who witnessed the chase slowed down enough for Kurt to jump aboard and then sped off, leaving his pursuers behind.

Michael Alexander, The Courier 08 Jun 2019

Soon after the fall of Czechoslovakia in 1939, Gruber manages to escape to Glasgow, with the intention to continue his political activity and resistance there.

Scotland

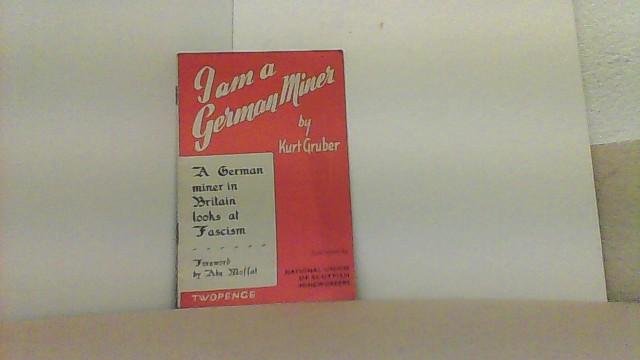

After a period of internment on the Isle of Man, Gruber was allowed to resettle in Glasgow, where he continued to work as a miner, joining the National Union of Scottish Mineworkers. During his time in Scotland, Kurt Gruber authored a pamphlet called “I am a German Miner” which was published with a foreword by trade unionist Abe Moffat, leader of the Scottish Mineworker Union and a leading figure among British coal miners.

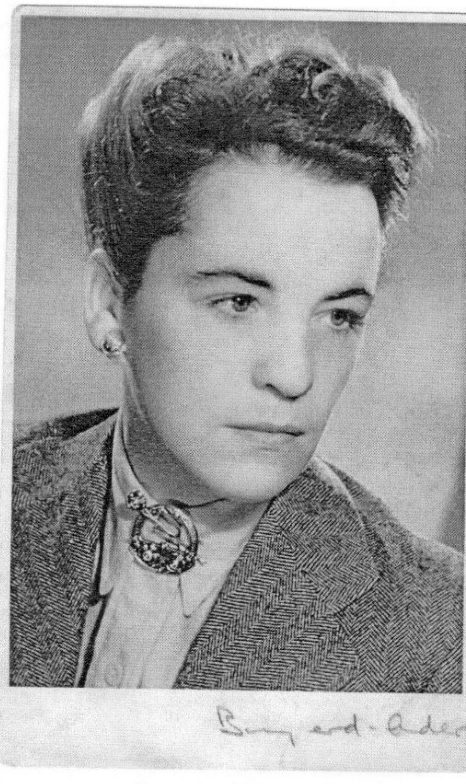

Kurt Gruber found solidarity in Scotland, and also found love. Jessie Campbell Leith was a Scottish woman who after leaving school at 14 worked as a secretary. She was subsequently involved with the local Communist party, where she met Kurt Gruber during anti fascist campaigning in Glasgow.

As far as I know Kurt and my mother fell deeply in love with each other

Catriona Joyce (Jessie Campbell Leith’s daughter from another marriage)

In 1944, Gruber was approached by the OSS to participate in a top secret infiltration mission into Nazi Germany, an opportunity he found hard to decline.

Kurt and Jessie married in a civil ceremony in Glasgow before moving to London to be closer to where OSS was based, in preparation for the mission. His recruiting officer would be Lt Joseph Gould, an American labour law expert from New York with proven experience in trade unions. Gould had been assigned to the Office of Strategic Services’ Labour Division. It was an office dedicated to the recruitment and training of dissident workers, trade unionists, and other civilian anti-fascist collaborators for deployment in a variety of stealth operations.

London

According to Lt. Gould’s memoir, Kurt Gruber was part of the small cadre of volunteers recruited among London’s Free Germans to be trained by the OSS at Franklin mansion in Ruislip (later known as the Battle of Britain House). They were men with similar background as Gruber : workers, trade unionists, and socialists : all united by their hatred against Nazis, and ready to risk their lives behind enemy lines. They also had the advantage of being native German, and by virtue of their OSS training and forged paperwork, would be able to mingle with the population at their point of insertion. Sure enough, Kurt Gruber was assigned to the mission codenamed CHISEL. The mission brief was insertion into the Ruhr Valley, where Gruber was to put his miner background to good use by reporting on the status of German industry and troop movements in the area. By March 1945, the Allies have already reached the Rhine at Remagen, facing fierce resistance – including wonder weapons such as V2 rockets and Arado 234 turbojet bombers, the likes of which have never been seen before ! The situation beyond the Rhine was completely unknown. Local intelligence was needed urgently, and therefore CHISEL got its go ahead for the night of the 19th of March 1945.

Final flight

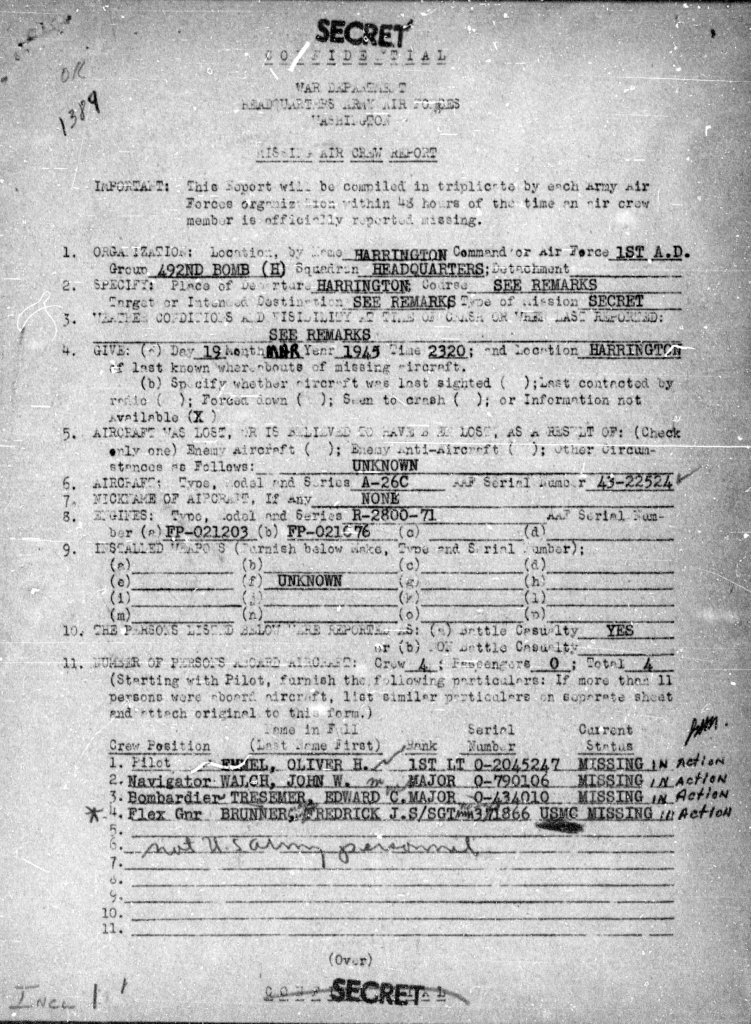

A Douglas A26 Invader light bomber was tasked for CHISEL, and a US Marine Sergeant called Fred Brunner was assigned as Kurt Gruber’s OSS jumpmaster. The rest of the crew were pilot Oliver Emmel, Navigator John Walch, and bombardier Edward Tresemer. They flew out of Harrington airfield, which had previously hosted Operation CARPETBAGGER, a series of successful supply missions to the aid of resistance fighters over occupied France in the prelude to D-Day. This is the story of what happened that night :

The drop date was set for 19 March. Lieutenant Commander Simpson was having trouble with the Air Corps, but his difficulties appeared to be waning. The problems with the Air Corps were largely those of coordination. The 492nd Bomb Group had thought it would be given a chance to fly regular bombing sorties after it had finished supporting the maquis in France. Agent dropping was both dangerous and unglamorous. Or so it seemed, until he learned that the plane scheduled to fly CHISEL was badly in need of repair and carried a faulty radio.

Usually OSS was placed in the position of asking the Air Corps to fly deep missions, but on this occasion the roles were reversed. Simpson wanted the flight scrubbed, but the Air Corps opted to “get it over with.” The aircraft was A-26 #524.. This plane had carried out the OSS HAMMER mission to Berlin some days earlier. Now it was sitting on the tarmac at Harrington with both engines torn down. Additionally, a storm was brewing and weather all the way to the target was forecast to be marginal.

The crew assigned to fly CHISEL had never worked together.

Lieutenant Emmel, the pilot, was not fully “checked-out” in the A-26. Nevertheless, a desk-bound colonel decreed that the mission would go.

At 2230 on the night of 19 March 1945, the glossy black bomber roared into the rainy sky and turned east. Its motors quickly droned into the blackness, and in a few moments, all that was left was the sweep of the wind and the splattering of rain drops on the oil-soaked parking stands. There were four crew members and the agent aboard. None was ever heard from again

Herringbone Cloak/GI Dagger: Marines of the OSS by USMC Major Robert E. Mattingly (1979)

Today we know that CHISEL went down in the early hours of the 20th of March 1945, after having encountered bad weather over Germany. The bomber crashed slightly NW of its indented target, somewhere in the marshes near the Westfalian town of Schwege, and just outside the farm of the Kruse family. Witnesses that have since passed away, reported that

the bomber hit the ground at a shallow angle around 1 o clock that morning, overturning several times until it hit a small stream. Five torn bodies were scattered near the wreck. The agent and a crew member were lying close to the hull, one body 50 meters away in a meadow, another was swimming in the water-soaked moorland. The fifth man must have been thrown away by the impact.

The crew of the plane that crashed wore military identification tags, while agent Gruber in civilian clothes carried a passport with him that identified him as Pavel Nowak with Czech nationality. Nowak had forged letters of recommendation and documents from the Hermann Göring works in Prague, which were supposed to take him to a factory in Mülheim.

After the crash, the police provided papers, templates, headphones and the microphone of a special miniature radio set, as well as 7000 Reichsmarks and a smaller amount in British pound notes. They turned the body over to the secret police.

Martin Frauenheim, German aviation expert an article by Westfälische Nachrichten, 09 Oct 2015

Aftermath

The CHISEL flight never returned, and by 06.30 that day it was presumed Missing In Action with all crew and passengers. Kurt Gruber was never mentioned in the official MIA report.

Back in London, Jessie was not told about Kurt’s disappearance until after the end of the war, presumably due to the secrecy of his mission. Her daughter Catriona recalls her mother’s regret about how “deep sorrow and distress” at the news of the disappearance of her loved one made her suicidal, and depressed. Around VE Day, as the rest of the world celebrated the end of war in Europe, Jessie suffered the miscarriage of her child with Kurt Gruber.

In January 1946, the US War Department acted upon a previous recommendation of the (by that time, dismantled) Office of Strategic Services, awarding a posthumous Medal of Freedom to Kurt Gruber. There was no ceremony offered, and none required :

The last episode in her story with Kurt that my mum described to me was of being escorted by the OSS to a black car, blindfolded and driven to a gracious but stuffy room where the blindfold was removed and she was presented with Kurt’s American Medal of Freedom and a citation noting his bravery.

We no longer have them. My mum always said that Kurt would have handed it back

Catriona Joyce (Jessie Campbell Leith’s daughter from another marriage)

Special thanks

- Michael Alexander of The Courier (Dundee) for Jessie’s story found in German anti-Nazi spy during the Second World War

- Eduardo Da Costa for his amazing photos from the Ardennes American Cemetery

- Jonathan S. Gould, son of Lt. Joseph Gould and author of German Anti-Nazi Espionage in the Second World War: The OSS and the Men of the TOOL Missions (Routlege 2018)

Some basic background information on ie Westfalia, the rise of the Nazi party, Trade Unionism in Scotland etc has been sourced on Wikipedia

A very moving and incredible story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am an employee of the Ardennes American Cemetery where these men are buried, and frequently use their story for my interpretive guided tours.

Platoon Sergeant Frederick Brunner was already a seasoned OSS operative, who had taken part in one of the Carpetbagger missions in Haute Savoie, along with Colonel Peter Ortiz. The reason why he was assigned as the jumpmaster for this mission is unclear. He was full fluent in German, which may be one clue, but Tools missions were not supposed to be executed in teams so he would not have jumped along with Gruber.

LikeLike

Hi Vincent. It’s very exciting to hear that the story of the doomed Chisel mission is being retold at the Ardennes American Cemetery. I am wondering whether you’d like to correspond with a view to exchange information, and perhaps arrange a small interview for my site?

LikeLike

This reminds me so much of my brave mum, Jessie Joyce (nee Gruber) who married Kurt during the war. She was utterly devastated when he failed to return from his mission, and was not officially told he was death for many months. Jessie told us many stories of Kurt’s bravery in trying to fight the Nazis inside Germany. Many ordinary Germans were appalled at what was happening and did their best to resist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Mrs Joyce, thank you so much for your comment. I have been researching Jessie’s and Kurt’s moving story for some time, and I am delighted this has attracted your attention. Would you be available to discuss their life more? I have an artifact related to Kurt I’d like to share with you. Please do contact me on explore@explorabilia.co.uk

LikeLike

Pingback: Flight of the Invader | Battle of Britain House