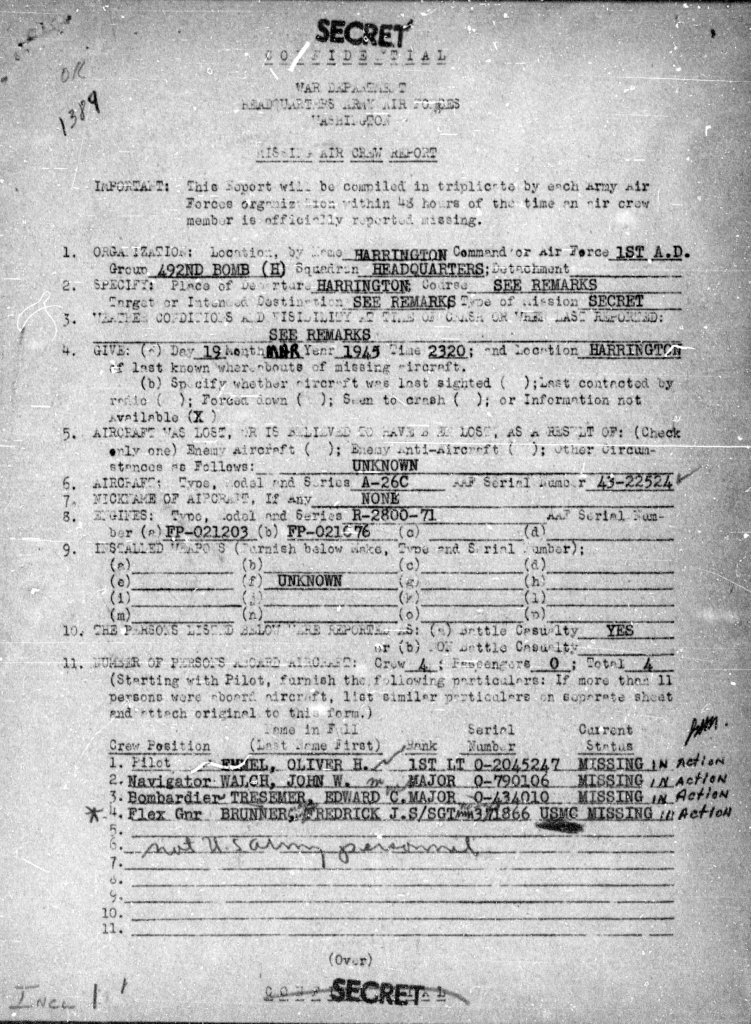

An interview with Barbara Kinnaird, member of staff at the Battle of Britain House

It’s a short drive to Wallis House, the retirement home where Barbara Kinnaird lives. At 98, she’s still a resident of Ruislip, a bright and pleasant lady who very kindly agreed to share her memories of working at the Battle of Britain House in the early 1960s – and who still does her own shopping in Ruislip High Street ! Barbara is quite possibly the last surviving member of staff at the mansion, and the stories and photos she shared open another window to the lost mansion’s nearly forgotten past.

Photos from the past

I met Barbara Kinnaird at Wallis’ House communal hall, and we dived right into looking at our photo collections. “I was the cook” , she relates, “and my husband Ian was the handyman and used to work in the garden. We both started in January 1961, and Ian eventually retired, then passed away on New Year’s Eve 1977 – I continued to work there until the mansion burned down in 1984. We lived in the cottages across the (Ducks Hill) road, and I would walk from there every morning”.

I show her this photo. “Oh yes, that’s me, with Millie and Mrs Stanyon. Yes, I got this photo too !

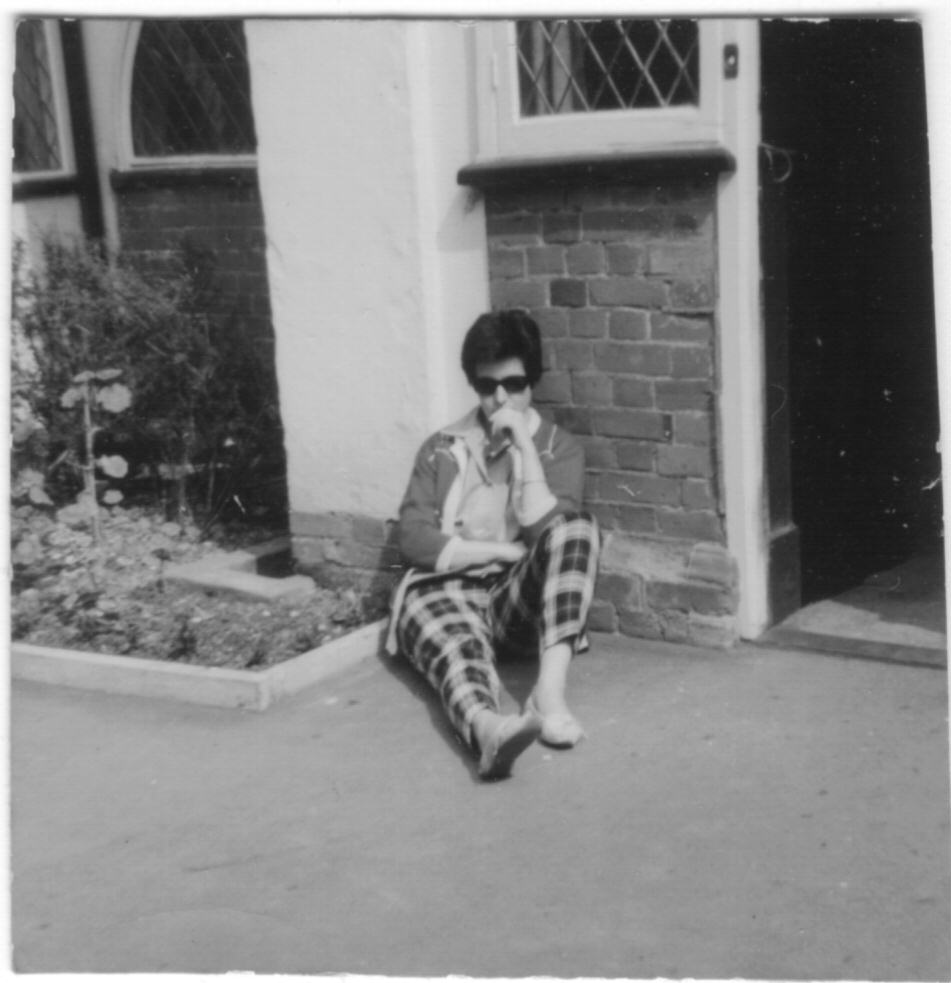

I ask her about the lady in this photo. “I think she was one of the various au-pair girls who helped – one of the Portuguese girls who met her future husband there – he was on a course at the Battle of Britain House. She met him there and they got married. I believe these photos are from when they got married, and we would be drinking to their health.” She’s Maria-Louisa”, I remind her. “Oh yes, that’s right. Marie-Louise (sic), she’s the one. She died a few years ago, I think. I don’t know about her husband – Seeger it was I think – I’ve forgotten the name.” Sid Owen – which I realize now might have been a pseudonym – is the fellow who sent me those invaluable photos, and probably the husband. I’m surprised he never mentioned he was actually married to Maria Louisa !

I show her the next photo. “Oh yes that’s my husband, and Len, and Harry, I think he was, in the garden shed having their break !” she laughs. “Ian was the handyman. Ken (sic) was the head gardener, and the others helped.

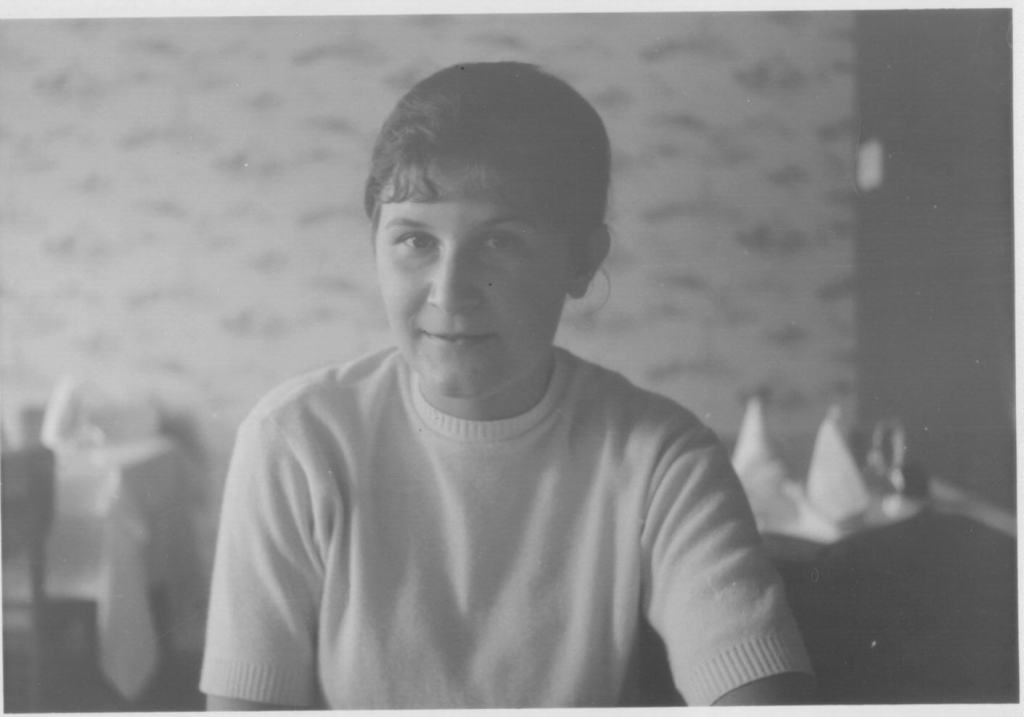

“Oh yes that was Karen. She was a German girl. I kept in touch with her until maybe two years now, I think she had so many heart problems and she died. But we always kept in touch, birthdays and Christmas, and she and her husband and children came over to England once or twice and came to visit me.” She the produces one of her own photos :

“That is the plaque that was it in the dining room, which says about the start of it. The dining room was panelled, and they had on one wall the shields of all the RAF Squadrons during the war”. This is a real interesting artifact – a photo of the actual the commemorative tablet placed there by the RAF staff who sponsored the creation of the residential college. I point out that this is the point when the house was renamed from Franklin House to Battle of Britain House. “Yes, I can’t remember the name, I’ve only heard the stories of the man who actually lived in Franklin House was an American – that’s why it was called Franklin House, Franklin Roosevelt, huh ?”

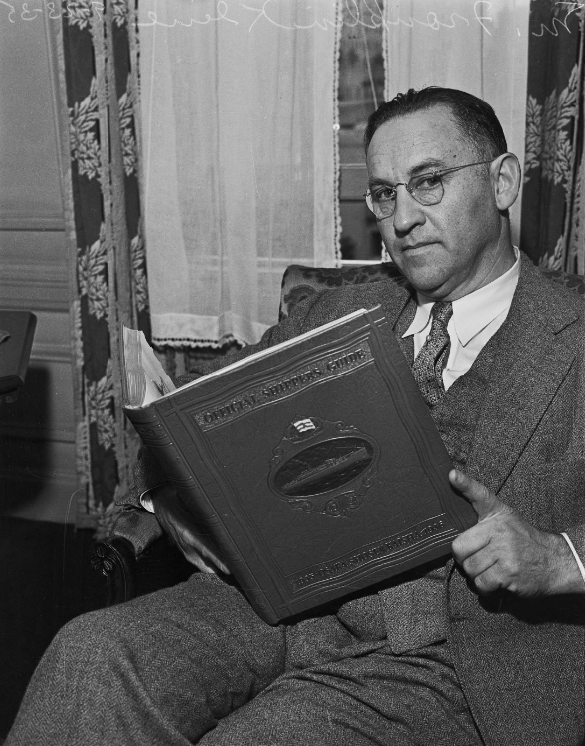

“This fellow here” – I show her a photo of Meier F. Kilne, the American writer who built the mansion. “Oh, I can’t remember the name. But it was said that he used to help Jewish children escape before the war, the so called Kindertransport. So the story was that he was involved in that.” This is another interesting revelation about Meier F. Kline, and an aspect of his life I’d never heard about before.

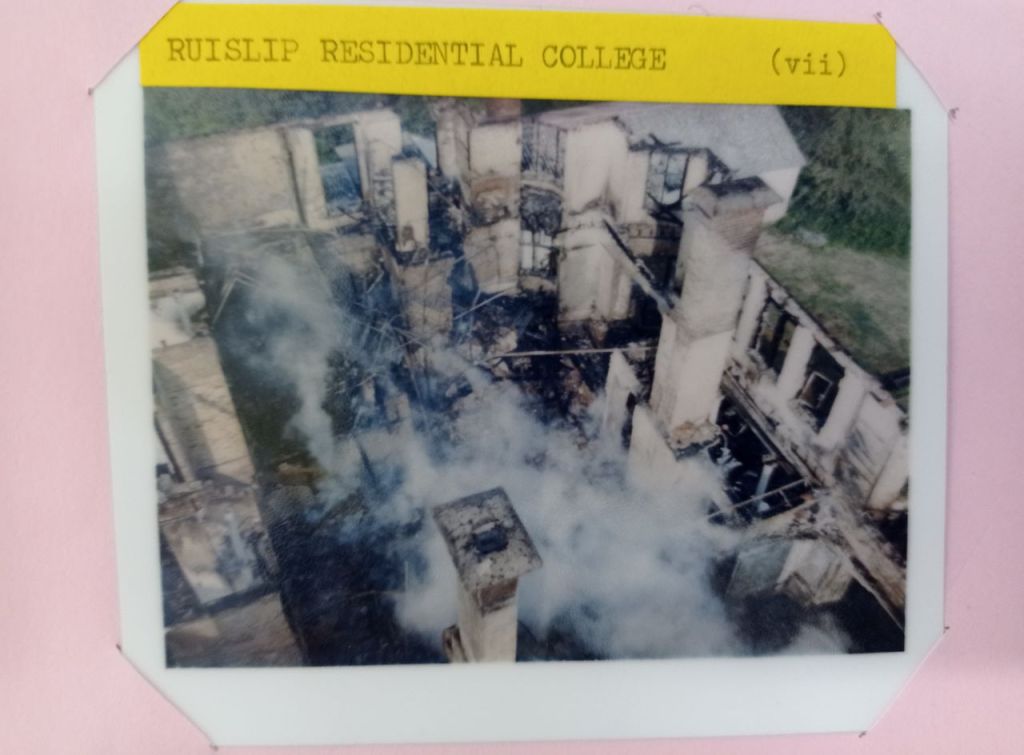

The Fire

I then ask Barbara about how she remembers the day of the fire that destroyed the mansion in 1984. “It happened in August, and we didn’t have any courses, everybody took their holidays in August. My husband had dies before then, but a friend would take me up to Shropshire, where I come from”. She remembers that as they came back on the end of the holiday and drew up to the cottage opposite the mansion’s driveway, there was a fire engine. you see. “I said – oh my goodness, I hope everything’s alright – and then we heard the fire. There was this panelling on the walls, and it was old. Mr Sale, who was the warden at the time, was out – so there was nobody in there, and I thought it was a passing policeman who saw smoke and called it in”

I explain about how I sourced the fire investigation report at the London Metropolitan Archive, which showed that the fire was a result of vapours from chemicals used to renovate the mansion being ignited by the pilot light of the mansion’s boiler – someone had the unfortunate idea to store those chemicals nearby. Barbara then surprises me with her response.

“It must have been at the cellar”, she says. “This is where the central heating was”

That’s an answer to a very burning question, if I ever had one ! “Was there a cellar?”, I ask. “Yes, there was a cellar, although I never really went down there. The cellar and the attic were places I never found myself in. My position was in kitchen”. At last, a confirmation that indeed a space exists in the mound under the ruin. It’s entrance must have been filled in at some point after the fire, but it’s certainly there.

“And of course there was the annex down the drive, which was a newer building with 20 or so bedrooms in it. And I think at a later time vandals did get in there, and there was drug taking or something like that, so eventually they demolished it as well”. A sad end for the last standing building in the grounds of the Battle of Britain House.

Characters from the mansion’s past

Another case comes to mind : “I have a particular question about a French girl who worked at the house”, I say. Barbara’s response is immediate : “Colette? Of course I remember her. We kept in touch until she actually died… She was very popular and friendly with everybody, and I think she quite enjoyed her time there. Her and her husband came over from France and visited me with Sylvie, their little girl. And she always kept in touch, wrote letters to me.”

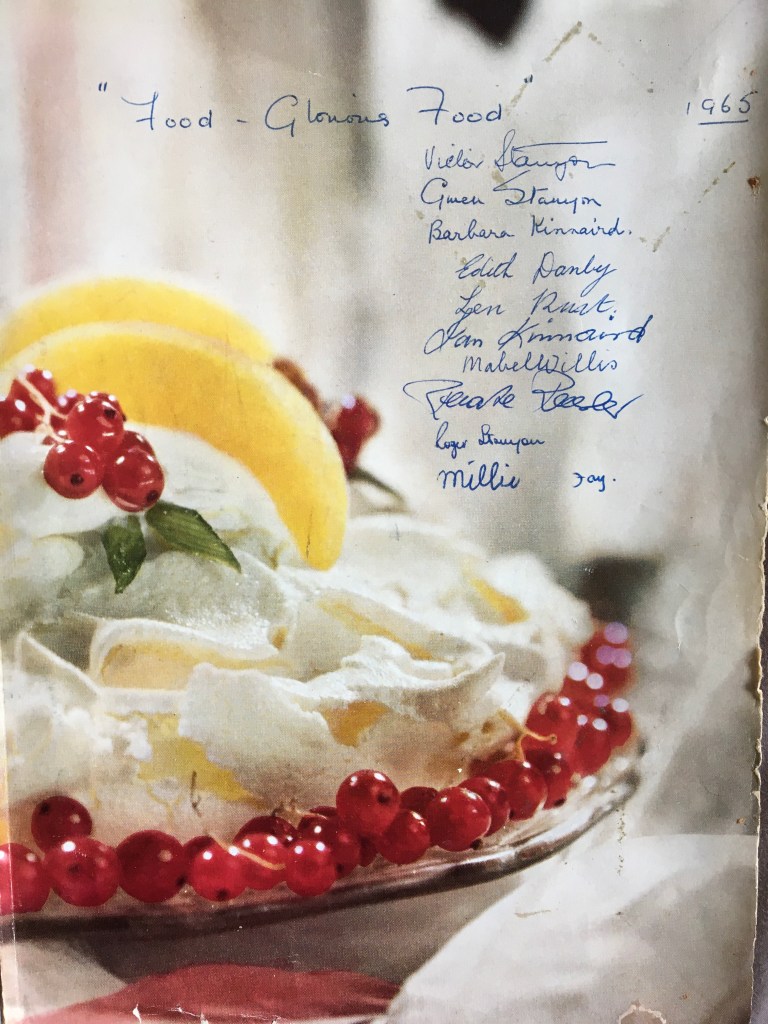

I mention how Sylvie had contacted me in the past, sharing details of daily life and important documents found in her mother’s diary in relation to her time at the Battle of Britain House. This included a signed recipe book presented to her by the mansion’s staff, including the dedications from Barbara and her husband :

Barbara is very pleased to hear Colette particularly praised the quality and variety of food prepared at the Battle of Britain House. The conversation the turns to the wartime history of the house. “Do you remember anything being said?” I ask. “Not much”, she admits. “That was way before my time at the house. There was just one occasion, I can’t remember what course it was, but we had a lady who came on a course and she said – oh, I recognize this house. She had been one of the people that they dropped over into France, like spies, or whatever they called them, the Resistance. But she’d been at the house, and they did training in the woods, and she recognized it, although she never actually knew where it was, it was all secret. But she recognized the place”. Another notable recollection from Barbara, which indicates that the mansion has also been used to train French Maquis for missions into France – very likely the 1944 Jedburgh missions, involving SOE/OSS personnel and French Resistance fighters operating in teams of 3.

The daily routine

The conversation now turns to the daily routine at the house. “I started at half past 7 in the morning to get the breakfast ready. Then the students came over for breakfast and they started lectures at 9 o’clock. Then I was preparing the lunch, of course, with help in the kitchen – they had that at 1 o’clock. They had afternoon tea, I used to make cakes with tea. And then they had the evening meal – although I’d finished work around half past 2, I went back across the road to the cottage, I came back again to work at 5 o’clock, to get ready for the evening meal, and finished about half past 8, then went back home again”

Barbara laughs “It was very busy !! Sometimes we had a course Monday to Friday, they went home after tea on Friday, and another course came in Friday evening for the weekend. And then I had a day off in the week when they had to take a spare cook from somewhere to take my place, otherwise I was off on Saturday and Sunday if there was no course. So it was very busy”. I ask whether the au-pairs helped in the kitchen “Oh yes. We had Colette, we had another French girl called Helene, we had a Spanish girl – Consuelo. There was the Portuguese girls, Marie-Louise, and another girl called Fatima, a Norwegian – Noreen, a Finnish girl – Haike I think she was. Yes, we had the United Nations !! she laughs. “Some of them could speak very good English, and some others, well.. I remember a Spanish girl, and Mrs Stanyon showing her around saying – and this here is A brown tree ! They tried to carry things on, but some times it was very difficult. I think it was through an agency they found the foreign girls, and then we had various local people like Millie who helped, either cleaning bedrooms or turning in the dining room and things like that”

Barbara is now showing me more photos from her time at the house, some of which I’ve never seen before :

“This is the staff at the house around the time we had the fire. This is at the back of the house looking down towards the Lido”.

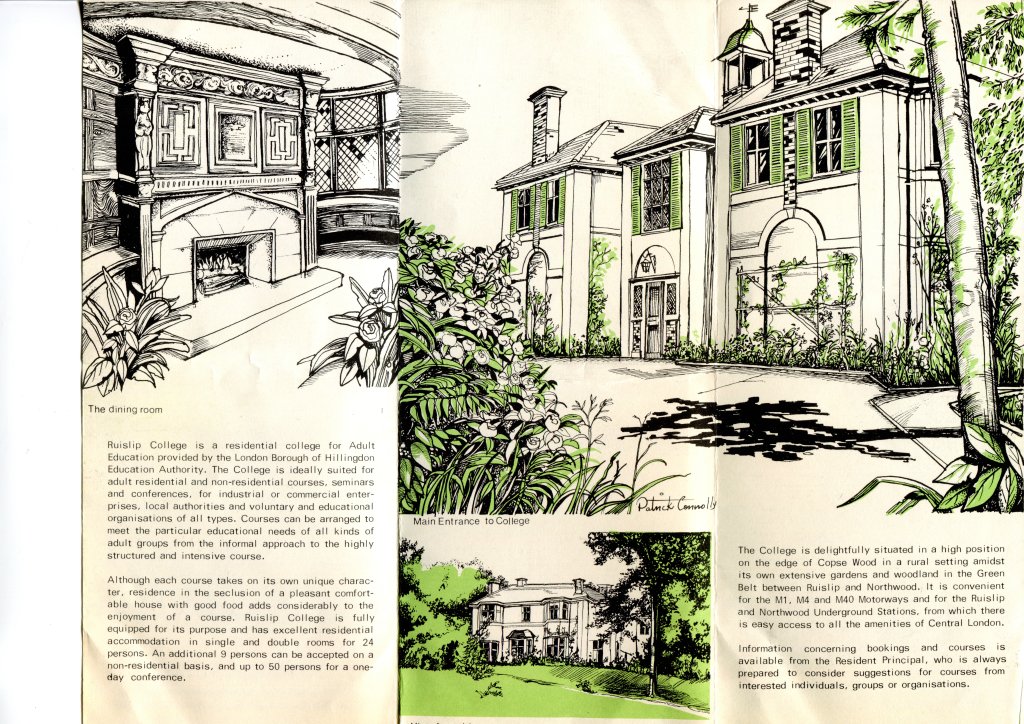

Barbara reminisces about the courses programme at the house “We had painting for pleasure, youth leadership training, and Laings the builders who had a lot of courses for their former employees – those who had gone into retirement. We had a folk group called The Spinners who came in over the weekends, and Claire Rayner – she lived in Watford I think – who used to be an agony aunt, as they call them, she came in too. I remember she came in one evening, and Mr Dalton who was one of the wardens said she had turned up like a ship in full sail, black sails too – for she was a large woman, and had that big black dress on !! We had Sir Adrian Boult, he did various courses on music. And we had the Rotary Club who held meetings there, and we had courses on nature – like the Natural History Society visiting. And we had one particular course who would get up at around 3 o’clock in the morning and go in the woods to hear the dawn chorus… oh I wish now I’d kept a list of all the various courses we had ! But had quite a variety of interesting things going on”.

Exotic Animals

My next question is about the cast metal statues which adorned the grounds, brought in the house by Franklin Meier Kline.

“Do you remember the lions and the elephant planters?” I ask. “Oh yes, yes I do remember. There was one lion on either side of the steps. I did hear that they’ve been stolen some time ago.. I don’t know if that’s true, but they’re not there anymore.”

“But that looks like Caesar, the old dog. When I first went to work there, we did occasionally have a health inspector who came around, and we had two dogs, Caesar and Timmy, and two cats – and the cats used to sleep in the kitchen by the boiler that heated the water. You wouldn’t be allowed to do that today, different health and safety standards! ”

Closing

I show Barbara some photos from the day of the fire, and recent photos of the ruin. I ask her whether she has visited the site since

“Oh no.. its so sad. I haven’t been around there since it burned down. Can’t imagine it like that now. I used to go around from Poor’s Field and the Lido to see the blue bells in spring, but haven’t been at the site, and I don’t visit the woods anymore”, she smiles. “It all seems so long ago… when we first came there, there were no street lights up Ducks Hill road, no pavement – there was just a hedge bank. Well there wasn’t so much traffic, but you just got out in the way, and hoped that no traffic was going by. No bus down that way, we had to go down to the bottom to get a bus. We lived in number 2 at the cottages opposite, and in number 1 there was an elderly couple (at that time) who seemed to know Kline, the man who built Franklin House. They came from Sheffield originally, and the man used to work at St. Bernard’s Hospital in Southall, and I think she also did at one time. They used to know a lot about the old history of the house and the area, from when they used to take things around in a horse and cart ! I haven’t been to the woods for years, but there used to be a scout camp in the woods. At one time in the evening, from our cottage, we could see the scouts with their torches, singing, going through the woods at night !!”

Last, I ask Barbara to walk me through the house as it was back then. “Well you went in the front door, and there was a big hall with a fireplace. To the right there was a library, then there was what they called the lecture room. The dining room was near the hall, then the kitchen, and then you went down along a corridor – I remember there were 2 or 3 big fridges there – and at the end, there was the sewing room, we had a lady who did the sewing and all that. Then the stairs went up and round, you could see the top, and there was a bedroom at the front for the warden and his wife, then there was a small bedroom with one bed, and another one with 4 beds in it, then another small bedroom – and a lounge and kitchenette for the warden and his wife upstairs. And round the other way there were two rooms for the au-pairs, who had a room each in those. I’m sure there was an attic, but I never went up there – or to the cellar !” She reiterates, laughing.

At 98, Barbara Kinnaird is well and sound, has a great sense of humour, and still does her own shopping at Ruislip High Street – make sure you say hi if you meet her ! Dear Barbara, my heartfelt thanks for offering your time, memories and photos. I’m wishing you well, until we meet again to share more forgotten stories of the Battle of Britain House.

- With special thanks to Mr Clifford Batten, Ambassador of the Middlesex, Spelthorne,Potters Bar and South Mimms Heritage Group for his invaluable help in making this interview happen