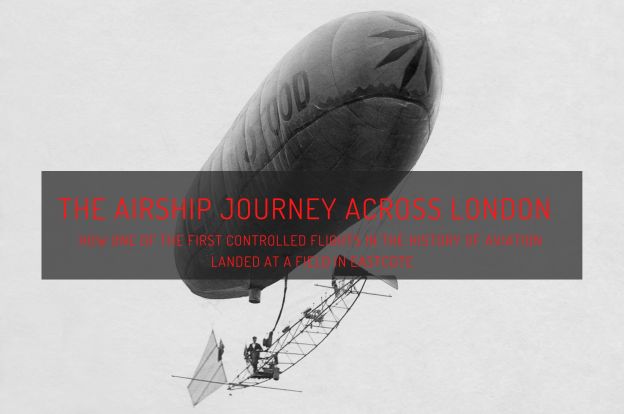

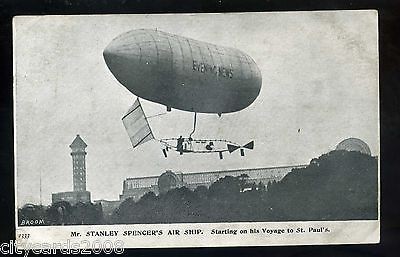

How one of the first controlled flights in the history of aviation landed at a field in Eastcote

In and around north western London, the frequent sightings of aircraft is a daily occurrence. Whether it’s London Heathrow, one of the world’s busiest passenger and cargo airports, or RAF Northolt, with its military and special flights, the skies above the borough of Hillingdon are alive with airplanes, keeping locals looking at the skies with curiosity, awe and pride. With all that aerial buzz over our heads, one could easily overlook how, long before airports even existed, a humble field in Eastcote hosted one of the first landings for a controlled, powered flight in the history of aviation.

Before powered flight was achieved in the late 19th century, our skies were somewhat quieter – although not entirely devoid of air traffic. Back then, early aviators endeavoured to conquer the skies by any means known to man. The French Montgolfier brothers achieved the first manned flight in a balloon in 1783, starting a race for aerial conquest among nations, which lasted well over a hundred years. By the second half of the 19th century, brave balloonists, aviators and parachutists had flown further than ever before, attempting increasingly bolder feats, and pushing the boundaries of manned flight further than ever before. Flying was as dangerous a pursuit as you might imagine : two Victorian balloonists, James Gleisher and Henry Coxwell, rose to an estimated height of 7 miles (11km) in 1862, miraculously surviving the cold (-20 C) as well as a deadly blackout for lack of oxygen. A Prussian named Otto Lilienthal met his death in 1896 falling from a height of 50ft (15m) and breaking his neck with one of his his experimental gliders strapped on his back. Despite the many dangers, those intrepid early aviators kept pushing the boundaries of manned flight forward throughout the 19th century.

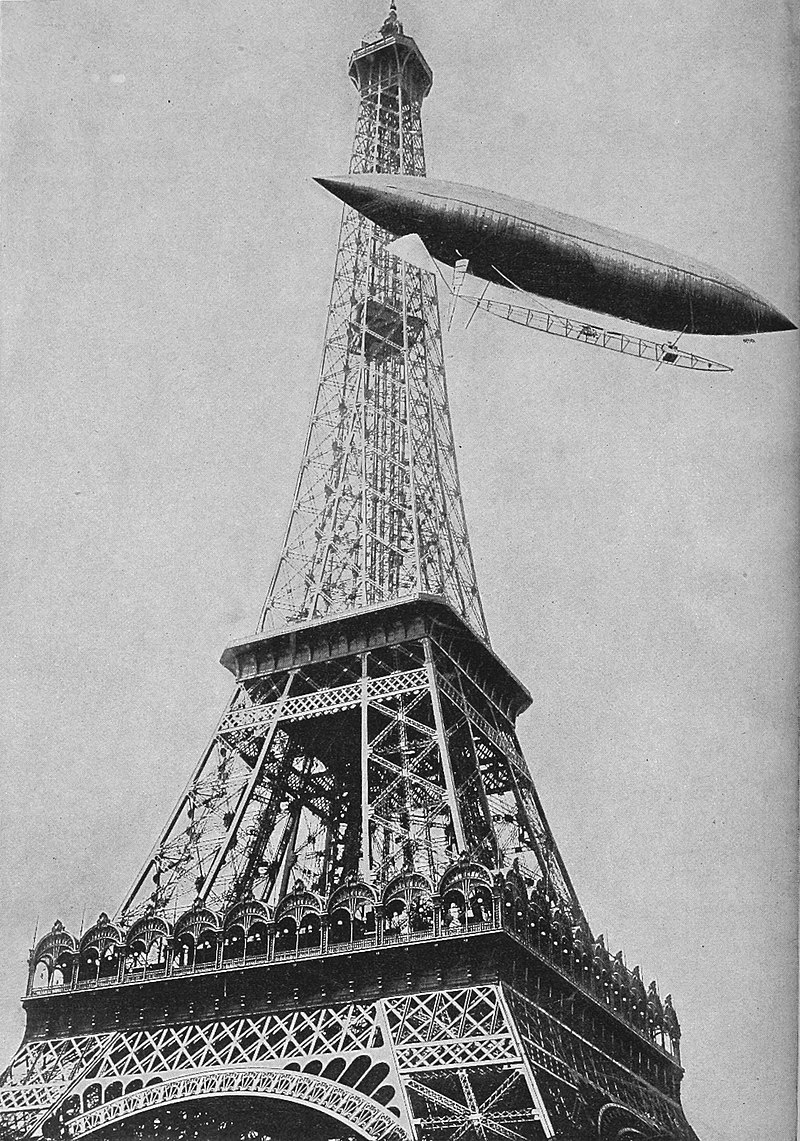

By 1900, aviators had mastered drifting in the winds in balloons, and instead focused their efforts to achieving controlled motorized flight. The vessels they used were dirigibles – elongated, lighter-than-air blimps fitted with steering mechanisms and combustion engine driven propellers. The race for controlled flight was led by the French-based Brasilian Alberto Santos-Dumont : he was a prolific designer and daring aviator, whose hydrogen airship – after several failed attempts – finally made the first complete steered and powered return flight in 1901, spectacularly rounding the Eiffel Tower in the process, as a jubilant Parisian crowd watched and cheered in awe. For that feat, he was awarded the prestigious Deutsch De La Meurthe prize for flying innovation, albeit not without controversy : despite the success of the flight, observers complained that Santos-Dumont had exceeded the 30 minute time frame permitted toward that record. A compromise was made when the aviator agreed to give his prize to charity. That tiny irregularity, however, meant that the prestigious record for a proper controlled, mechanized flight was still up for grabs.

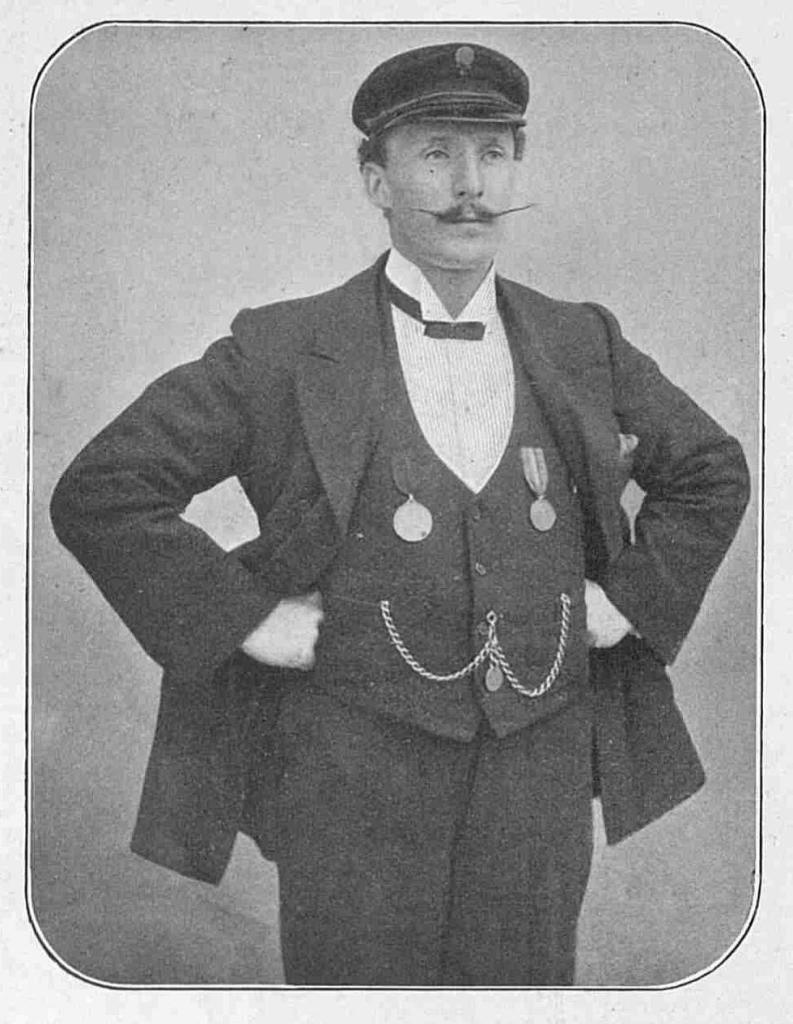

Stanley Edward Spencer – legendary English aeronaut

The news of Santos-Dumont’s ‘failed’ try reached the workshop of Stanley Edward Spencer in London. He was a well known English aeronaut, coming from a family of early aviators. His grandfather had flown balloons since 1836, and his father was a gliding pioneer who owned CG Spencer and Sons, a balloon factory and workshop in Holloway, London.

Stanley and his brothers were all accomplished aeronauts and parachutists who frequently operated in the boundaries of physics, flirting with mortal danger. Before 1900, Spencer still experimented with balloons, having performed several daring feats such a 5 mile (8km) ascent in a hydrogen balloon, and a number of close observations of astronomical phenomena from above the clouds. He was an aeronautical celebrity who spent his time designing new flying machines, and then adventuring around the world, demonstrating their capabilities or giving lectures to curious crowds. Spencer once demonstrated balloon flight to the Mughal Viceroy of Murshidabad, who almost forbade him to fly, fearing that he might break his neck before he had sampled the exquisite harem he kept. In Punjab, a jubilant crowd followed his descent to greet him as he landed – and running off with bits of his balloon and gondola as souvenirs. On another occasion, Spencer survived a 600ft (180m) fall when his balloon collapsed in Hong Kong, narrowly escaping with just a broken leg. And he almost drowned twice ballooning in South America, losing all his belongings at sea, and resorting to handouts to get back home. He then made his way to China, at the behest of a local mandarin. Balloon ascents had never been performed in China before Spencer, whose balloon rose above the ground amidst huge crowds, causing a stampede where several people lost their lives. His second ascent in China inspired such excitement – and confusion – about manned flight in the local populace, where many began throwing themselves off their roofs to try to emulate the feat… Spencer became proficient in raising money from the sale of tickets to his lectures and demonstrations, as well as in securing funding from enthusiastic patrons around the world. He then invested it all back into his next designs and record-breaking attempts.

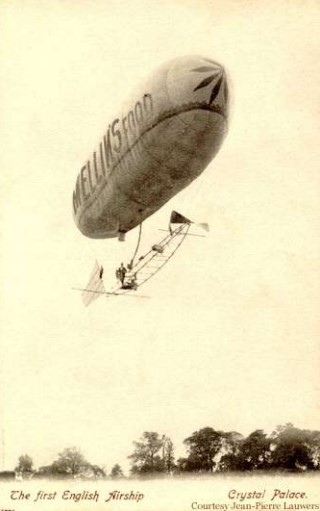

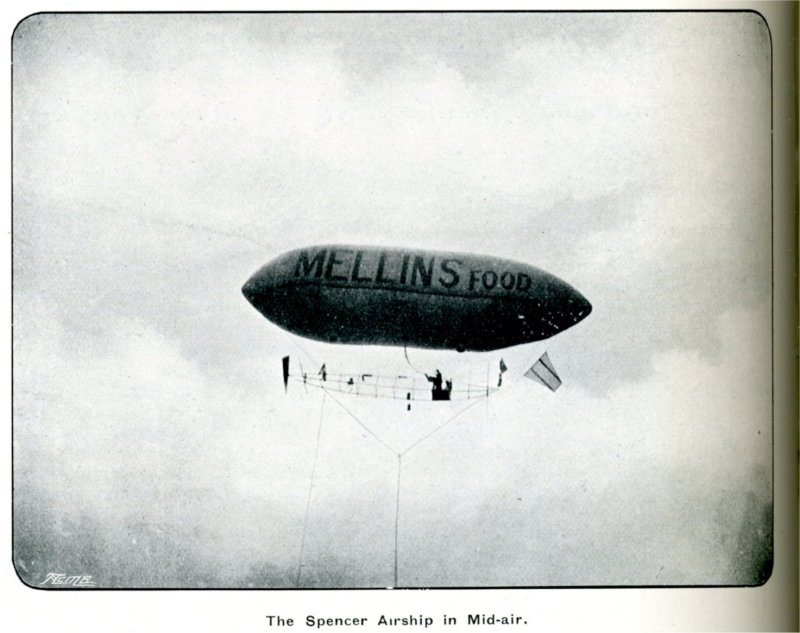

Upon hearing the news from Paris, and seeing the photos of Santos-Dumont’s questionable attempt, Spencer immediately changed his focus from balloons to the new, up-and-coming field of controlled dirigibles. He believed he could build a superior motorized dirigible to that of Santos-Dumont, and set about launching an effort to sustain a much longer controlled flight with it. To fund his experimental flight, he entered a sponsorship deal with Mellin and Co., the manufacturer of a popular infant formula. In return for the sum of £1500, Spencer agreed to display the Mellin’s Food brand logo across his dirigible’s hydrogen envelope for the next twenty-five return flights of his dirigible.

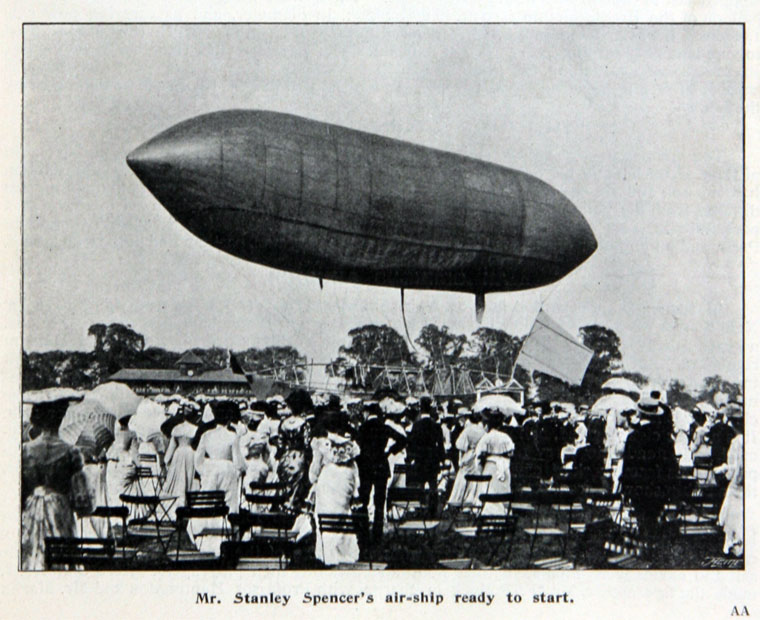

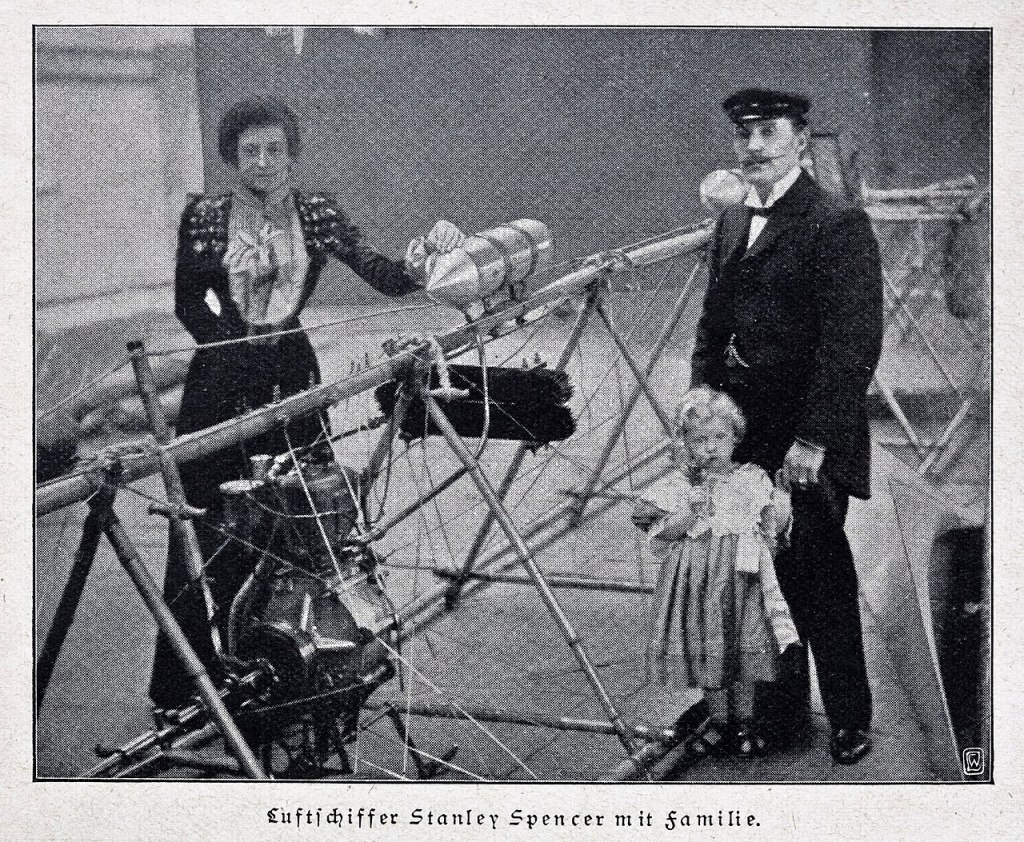

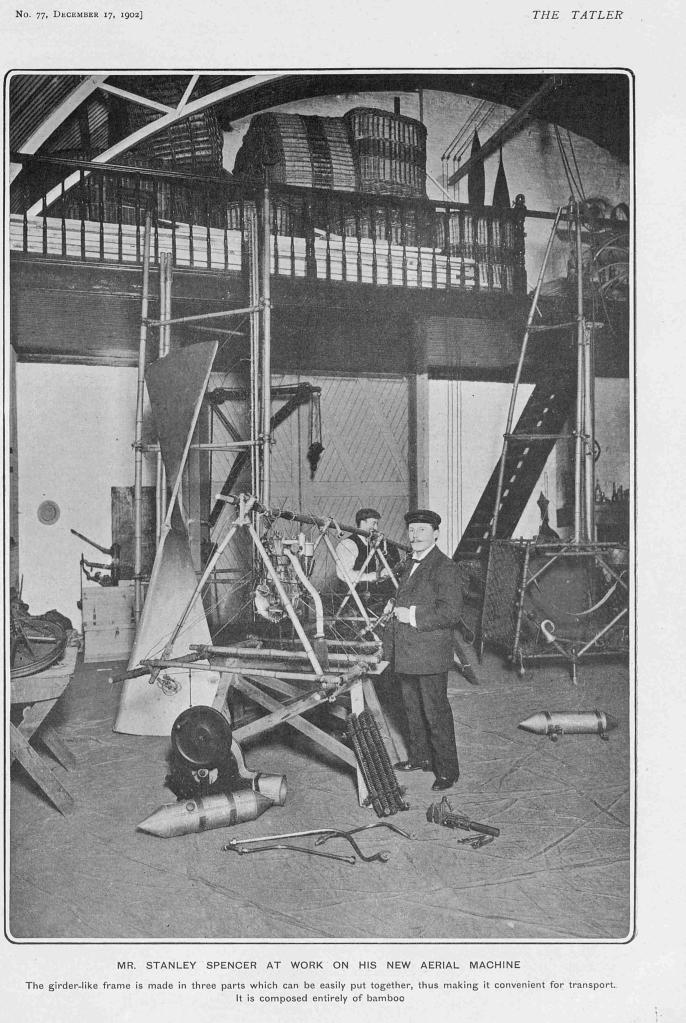

Spencer opened a new workshop at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, and set about creating his dirigible. The 75ft (23m) hydrogen envelope lifted a light bamboo frame. The airship carried a 3.5hp Simms combustion engine that powered a forward-mounted wooden propeller, and featured a sail-like steering mechanism (for comparison, a Spitfire MkI, introduced 35 years later, poured just over 1000hp out of its Merlin engine…). There was space for just one person on the rickety flying contraption : it would of course be Spencer himself – although his wife Rose is also known to have test-flown the airship (untethered, imagine..) over the workshop.

Spencer’s original plan was to take off from Crystal Palace, fly around St Paul’s Cathedral, and return to Sydenham – effectively doubling Santos-Dumont’s flight distance from the previous year. After a number of trials above Crystal Palace – one of which included his 3 month old daughter as a passenger – Spencer set off to break the record of controlled, powered flight on the 19th of September 1902. Here’s a contemporary account of the historic flight that took place on that day :

The Times, Monday 22 September 1902

“Mr Stanley Spencer, the aeronaut, who in Friday crossed London in a navigable balloon, informed a press representative that he had been waiting for some time past for sufficiently favourable conditions to enable him to make an extended flight in the “Mellin” airship with which he has been experimenting for the past 3 months at the Crystal Palace.

He came to the sudden determination to make the venture of Friday afternoon on finding that the wind was almost due south and that apparently fog was altogether absent. Casting off at about 4 o’clock, he rose at an altitude of at first 300ft, cleared the Palace, and headed the vessel, which was entirely under his control from first to last, in the direction of the City.

The 10ft propeller, driven by a Simms petrol motor, was working smoothly at about 200 revolutions a minute, and the rudder acted readily, but Mr Spencer found just as he was passing across Loughborough-junction that the balloon was steadily rising and that the great silken envelope above was gradually becoming more distended as the expansion of the gas increased. The vessel had never before been tested in a prolonged flight, and consequently it was a moment of anxiety for the aeronaut when he found that the safety automatic valve, which is provided to allow of the escape of the gas when it has exceeded a given limit of pressure inside the envelope, shoed no indication at first of acting. Mr Spencer was just about to open the valve at the top of the balloon by a rope from the car when the automatic valve opened and the baloon was relieved.

At this juncture the aeronaut found that his further progress across the City was rendered impossible by a bank of mist, so he directed his course by two or three degrees to the westward, his vessel crossing the river at the Victoria-bridge, Chelsea. Here, for the benefit of several hundred spectators on the bridge and along the Embankment, he tested the balloon’s manoeuvring capacity by executing two evolutions directly over the river,and, continuing his hourney across the Earl’s-court Exhibition grounds, repeated the experiment.

Mr Spencer describes his impression of the spectacle of thousands of people looking up at him four or five hundred feet below in every attitude indicative of astonishment and wonder as one of intense amusement. From Ealr’s-Court, all mechanism still working smoothly, he passed on across Hammersmith, Chiswick, and Ealing, at each of which points he made short circular flights, an proceeded with a velocity of about 7 1/2 miles an hour to Acton where, as dusk was commencing to set in, he began the descent.

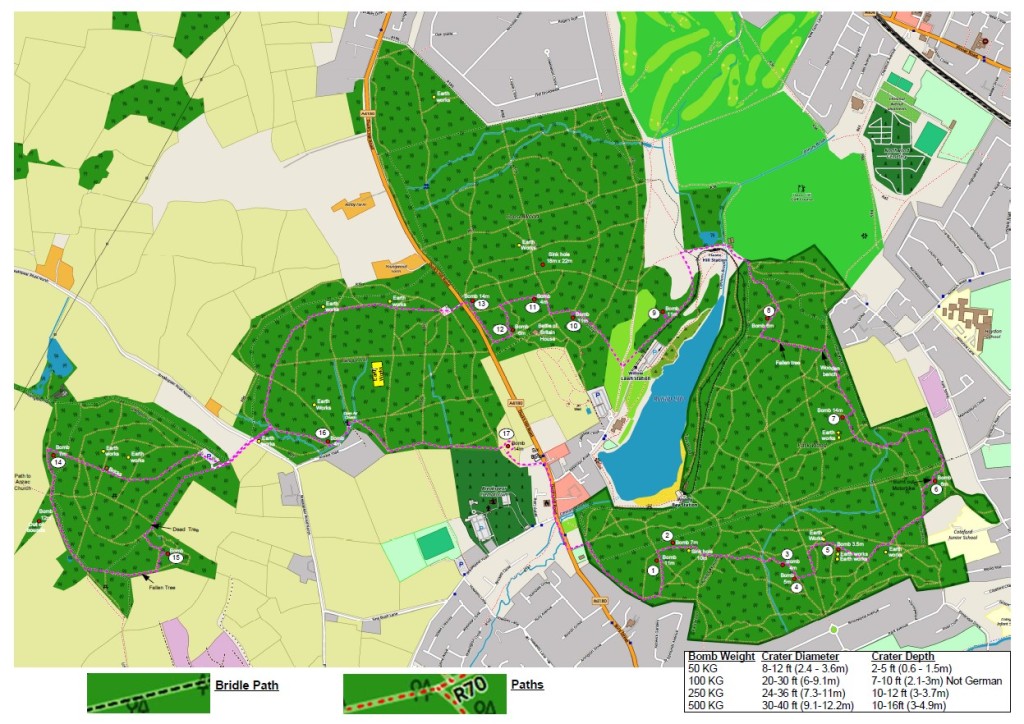

This, in Mr Spencer’s balloon, is accomplished by the gradual displacement of the hydrogen in the balloon by means of a species of enclosed fan, operated by a handle within easy reach of the aeronaut which pumps, under low pressure, the ordinary air into the envelope, the superfluous hydrogen being discharged at a rent in the side of the balloon. Descending by gradual degrees the vessel came to the ground in a field at Eastcote, near Harrow, and Mr Spencer terminated his remarkable journey without having sustained a single mishap or the least derangement of his somewhat delicate propelling mechanism.

He expresses himself completely satisfied as to the capacity of his vessel for successful navigation, and is confident that, given the necessary atmospheric conditions, he could reach any point over London from the balloon-shed at the Palace and return to the starting-point. The present size of the balloon allows, however of only two hours’ supply of petrol being used.”

Spencer’s further adventures

Owing to the fog rising over the City, Spencer didn’t manage to circumnavigate St. Pauls’ Cathedral on that day. In true daredevil fashion, however, he decided to push on for as much as he could instead, flying over 17 miles (27km) across London, and landing at a field in Eastcote at dusk. His flight that had lasted a record 3 hours, near the limit of his fuel tank capacity.

Spurred on by his success, Spencer continued his much publicized airship feats. On the 21st of October 1902, less than a month after his flight over London, he re-assembled his airship at Blackpool, where in front of a crowd of 13.000 people, he navigated it through strong winds, landing near Preston. The same November, he took the ship across the Irish Sea, from the Isle of Man to Dumfries. Soon, however, his relationship with his sponsor would become strained. Mellin & Co. took him to court for being unable to keep up with his end of the deal for “25 return flights”, withholding the last £500 from the agreed sum. After an argument about what constituted a ‘return flight’ for the purpose of the contract between the two parties, the court ruled in favour of Mellin & Co. This sum still seems like a drop in the ocean, given the actual cost of his many exploits was much, much greater. For comparison, the cost of his showing at Blackpool set him back circa £450, while his income from the event was approx. £200. Spencer, like many adventurers of his time, prioritized his personal quest for glory over other practicalities – such as money.

Unperturbed by this unfortunate turn of events, Spencer began work on a second, larger, and more powerful dirigible. The Spencer MkII blimp was 88ft (27m) long, powered by a 35hp engine (10 times more powerful compared to the first) and twin propellers designed by Hiram Maxim, the inventor of the machine gun. The new contraption, however, crashed upon take off in Surrey, suffering a broken propeller. Spencer converted the MkII into a single-propeller craft soon after, and securing a sponsorship from the London Evening News, he attempted another circumnavigation of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral on the 17th of September 1903, almost a year after his historic first attempt. Unfortunately, that effort was also unsuccessful : beset by strong winds, the airship managed to complete half the ‘evolution’ (as he called it) around the dome before turning to the north, eventually landing near New Barnet.

It is said that Spencer planned a third, even more powerful airship. It would be 150ft (46m) long, powered by two 50hp engines, and would carry 10 crew and passengers in its gondola. But time was running out for the adventuring aviator : with his various debts mounting up, and Mellin’s Food still pursuing their claim, he declared bankruptcy in April 1904. In January 1906, Spencer was on his way back from India on the liner City of Benares, when he was taken ill, disembarking in Malta. He was diagnosed with typhoid fever, and died on the island on the 26th of January 1906, leaving his wife Rose and daughter Gladys destitute. Thankfully, the good standing of the Spencer family in the community helped young Gladys earn a place at the Orphan Asylum in Watford in 1907, where she was educated. Its notable main building is Grade II Listed, and can still be seen near the Watford Junction station, having been converted into a housing estate. Gladys passed away in California in 1993, at the ripe age of 91.

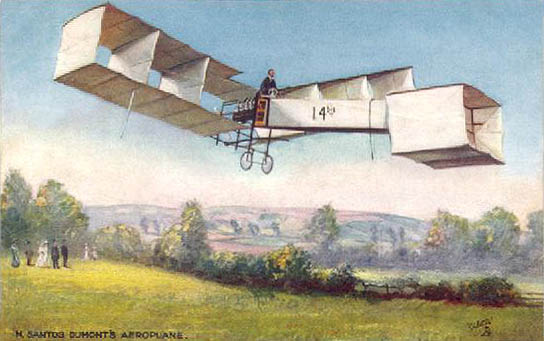

As for Alberto Santos-Dumont ? His obsession with flight and the success of the Wright brothers in taking to the skies with a heavier than air machine at Kitty Hawk, NC in 1903, saw him turn his attention into building his own airplane, the 14-bis. On the 23rd of October 1906, he managed to fly in a controlled manner for the grand distance of 60 metres with it, in front of a jubilant crowd : the first powered flight with a heavier-than-air aircraft in Europe. Santos-Dumont built increasingly better and more powerful machines until 1910, when he announced his retirement from aviation. What people initially thought as exhaustion, was actually depression over the onset of multiple sclerosis.

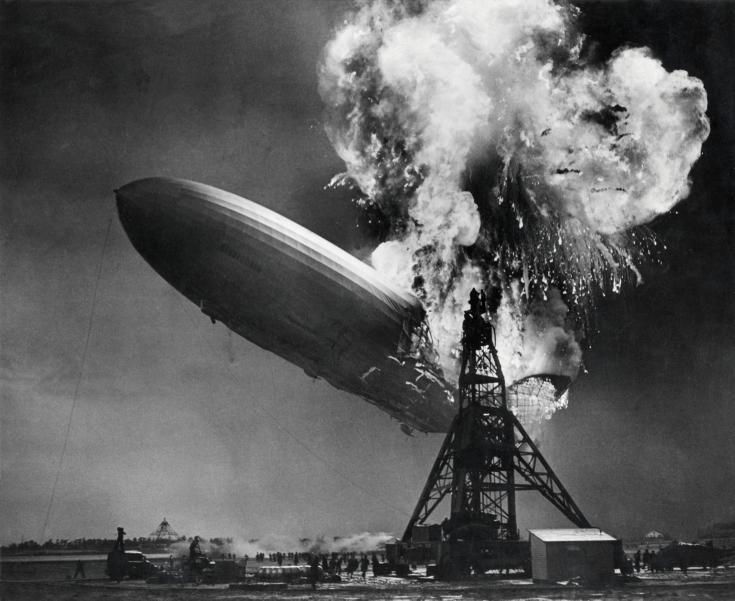

Airships and aircraft of ever-increasing size and power would continue to improve throughout the first few decades of the 20th century. You can read a bit more about how the technological leaps made by those early aviators were eventually put in deadly use during World War I – and in every subsequent war since – in my post named To Catch a Gotha, where I present the dramatic story of the first aerial bombardments that took place during the late stages of the Great War. Alberto Santos-Dumont took his own life in 1932, depressed by his worsening illness, as well as the realization that he had helped to invent a new implement of war, prompted by the use of aircraft in his native Brazil’s Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932. The final episode of that romantic era came only a few years later with the 1937 Hintenburg Disaster, an event that irrevocably shook public confidence in blimps, signalling the end of the airship era once and for all.

Sources :

- Mr Stanley Spencer’s Invention, article United Press Association, 22 October 1902

- Stanley Spencer’s Airship No1 makes first powered flight in Great Britain

- Stanley Spencer’s Airship Flight from Blackpool October 21st 1902 by Colin Reed

- The Airship Journey Across London, article at The Times, 22 September 1902

- The Victorians who flew as high as jumbo jets

- Various biographies, dates, references and public domain photos from http://www.wikipedia.com